It was one of those moments where you find your palm clapping up against your forehead. When an evasive, niggling feeling that something is off pivots into a blinding flash of the obvious.

I was sitting in a Situational Workshop (SW). An SW is a twice-monthly meeting where six peers—a cohort—come together for 2 hours to support one another in their personal development. I was observing this one, the 14th and final one of the week. Literally, the 27th hour. I was bored out of my mind, and here’s why…

In an SW, each person is to bring—

- A challenging situation where

- They intentionally did not do their typical, counterproductive behavior

- And did what might be a more productive behavior

- In spite of the awkwardness, worry, anxiety, or fear that triggered

- In order to learn about their emotions and thoughts—to gain self-knowledge.

You might want to read that again and let it sink it.

If a person brings that, it isn’t boring. And I was bored…

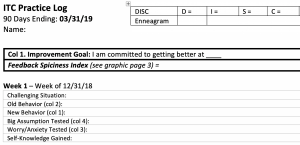

Each person coming to their SW captures the above in a simple form, presents the situation including what they did, what they experienced, and what they learned. I’ll attach a screenshot to the left of what that looks like.

Each person coming to their SW captures the above in a simple form, presents the situation including what they did, what they experienced, and what they learned. I’ll attach a screenshot to the left of what that looks like.

They then fall quiet, and they get feedback from their peers. The peers play a very special role—to practice radical candor. It’s a tall order, and it starts out very imperfect and can take years to get there. But every step towards it tips the scales towards an entirely different experience.

Radical candor is a potent combination of breathtaking candor combined with psychological safety (unconditional support). It is very, very unusual in the world today. We tend to be indirect, but kind. Or direct, but unkind. Both directness and kindness in equal and high doses is not easy. But it is the single most important element of a successful peer development group, and an essential ingredient if we are to gain self-knowledge. Why?

Have you noticed how easily we see into other people’s blind spots, but that it scarcely occurs to us that we even have one? Radical candor fixes that.

In an SW, we make a deal with one another. An explicit one. “Help me see into my blind spot, and I’ll help you see into yours. It won’t always be comfortable, but we will always care for one another.” This is an atypical relationship. It is…

“Let’s be training partners.”

Typical relationships are often based on a very different, implicit agreement. The agreement is more like “if you don’t call me on my stuff, I won’t call you on yours.” You could call that “let’s be nice.” A.k.a…

“Let’s be partners in crime (supporting one another in our weaknesses).“

A group of people working in an SW is what Sara calls a peer development group. Such a group is challenging to set one up and get right (and keep it right), but boy when it starts firing on all cylinders, it is magic.

The SW I was sitting in wasn’t magical that day. Far from it. And I had a niggling feeling why, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on it. Not at first. Turned out I was struggling to because I was actually a big part of the problem.

(Yikes.)

It went down like this. Look back at that screenshot of the form. What do you see as the last item? “Self-Knowledge Gained”

The person reporting on her situation said,

Well, I learned that in this situation, I should do this behavior and not that behavior!”

That was the moment the flat of my palm literally found my forehead. (Yes, everyone looked at me quizzically.) This person had done what I’d seen about 63 other people do that week…

She had identified a behavior that would serve her better. What’s the problem with that? In and of itself, nothing. Good to know, and may be quite helpful.

But.

That is not self-knowledge. Not the way I define it. And that, that was where I was contributing to the problem.

I had explained along the way that the purpose of the SW is to gain self-knowledge… but I’d never defined what I meant by self-knowledge. And most everyone was thinking self-knowledge meant becoming more clear what behavior they do by default and selecting a behavior that works better.

That is self-awareness, maybe. But not self-knowledge.

Over the Christmas break, a couple of weeks after palm-to-forehead, I realized I needed to define self-knowledge. Further, I realized that we had 180 people in 29 cohorts working in these twice monthly SW’s that I needed to set things right with.

Here’s how I defined self-knowledge…

Gaining self-knowledge means gaining a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the “internal operating system” (IOS) that gives rise to our counterproductive behavior and, often, our internal state. That “internal operating system” includes three aspects—mental (thinking), emotional (fear), and instinctual (physical impulses).”

So now I have three things to share with you in this article:

- Self-awareness versus self-knowledge

- Knowledge of behavior versus self-knowledge

- A tell-tale sign of the people in an SW losing their way

Self-Awareness vs. Self-Knowledge

I’ll come right out of the gates and tell you that some people will disagree with the distinction I’m about to make. I’ll also tell you I’m a-okay with that.

Self-Awareness—the way I see it—means to be aware of your self. One definition online puts it this way:

Self-awareness is conscious knowledge of one’s own character, feelings, motives, and desires.”

Self-awareness is a good thing to have, for sure. I’m all for it. Much better than nothing at all. But it falls short. It is insufficient.

There is a scene in one of the movies in The Matrix trilogy I just love. It is a scene where—after a fight ensues—the two combatants bow to one another. The dialogue goes something like this (but don’t quote me on it).

“Why did you fight me?”

“To find out who you are.”

“You could have just asked.”

“You don’t know someone until you fight them.”

This is something like the difference between self-awareness and self-knowledge. Here’s what I mean by this.

Go back to my definition of self-knowledge. To “gain a more nuanced understanding of the ‘internal operating system’ (IOS) giving rise to the counterproductive behavior and internal state.”

You cannot gain self-knowledge unless you—as we used to say in the south—“tangle with it.” Unless you tangle with that IOS. A struggle ensues when you provoke your IOS, and then you will tangle with it, and you learn about it. There isn’t any other way.

We can’t see our IOS directly. It’s in the back room and the lights are off. And the door is locked. And it doesn’t answer to a conventional knock-knock. There is no, “Who’s there?”

Until.

You meet your internal operating system the moment you deny it the behavior it is designed to drive. In other words, when you intentionally “don’t do” the behavior it normally drives, it freaks out a bit. The door swings open to that back room, and the Wizard of your Oz emerges (sometimes roaring) to sort things out, restore order, and set things right in your world again. To put you “back in line” with the program…

Through fear. Through thoughts and feelings like, “If you continue on this course, knucklehead, you will die.”

Well, if you persist and don’t capitulate to the old behavior, you find out if that is true. And it usually isn’t.

Over three years, most of the 180 people in 29 cohorts I’m working with have intentionally “not-done” a default behavior at least once, felt like they were going to die, and didn’t. Further, they gained some insight into the thoughts that have been giving rise to the old, counterproductive behavior. In tangling with their IOS, they gained some knowledge of it. That’s self-knowledge. The start of it, anyways.

I wish I could tell you it always goes swimmingly from there. It doesn’t. Far too often, after one good rush like that, participants go back to not-so-challenging tests, wandering around in their comfort zones, and wonder why they and their cohort become bored silly with their reports.

You can call that a lack of radical candor from the cohort members. You can see it as the effects of the incessant gravity that causes a peer development group to drift back to the more conventional way of relating. The partners-in-crime mode.

Radical candor is the antidote to boring SW’s. If my report is boring to you, and you summoned radical candor, you might say, “Otis, I have to say I’m finding myself bored silly with your recent tests. Most especially this one. Tell me… I’m truly curious… did this test push you outside your comfort zone? I don’t get any feeling for that at all. What am I missing?”

The difference between self-awareness and self-knowledge is experience. Self-awareness can be gained through study, the help of a therapist, reflection, and the like. Self-knowledge includes all that. It also includes the experience of defying the IOS, watching what happens, and evaluating the IOS for flaws. It is experiential. As we shall see here, self-knowledge is often gained through discomfort, and most of us are pretty skilled at moving in the opposite direction of that.

Notice above I said, “the start of it, anyway.” The example above was ONE encounter with the discomfort zone. ONE encounter with the unknown. Was ONE provocation of the IOS. Was ONE near-death-experience. While it is amazing and absolutely necessary, ninety-nine percent of the time, ONE is utterly insufficient.

Self-knowledge requires repeatedly leaving the comfort zone. People that become adept at it begin to see it as a way of orienting towards life—choosing to leave the comfort zone again and again. They see it as an ongoing process of pushing their comfort zone outward, mapping out their discomfort zone… making the unknown that lies in the discomfort zone, known. Shining their flashlight on the monsters underneath their bed.

Bottom line. You can possess self-awareness without ever changing a counterproductive behavior. In fact, you can use self-awareness to justify continuing your counterproductive behavior. “That’s just the way I am. Read my DISC. Read my Enneagram. Talk to my therapist. I’m just being me.”

Bull crap.

Self-knowledge is quite different than that. Self-knowledge enables a continual march towards the highest expressions of ourselves—love, wisdom, compassion, right action. It never involves justifying poor behavior, personality traits, etc.

Self-knowledge is power. No one can give it to you. No one can take it away.

Knowledge of Behavior versus Self-Knowledge

Now that we’ve sorted out what self-knowledge is, this second thing is easy.

Back to the palm-to-forehead moment, where the person said, “The self-knowledge I gained was that in this situation I should do this behavior instead of that behavior.” She had gained knowledge of her behavior, but not self-knowledge.

What would self-knowledge have looked like? We might have heard her say…

In not-doing that old behavior, I felt a moderate amount of anxiety. It was hard to overcome, but this time, I managed. I noticed as I was doing the new behavior, that I started thinking ____. I’d never noticed that thought before, yet I feel like it has always been there, you know?

The new behavior did appear to work better than the old behavior. I felt better about it, and the people involved seemed to as well.

So what I learned was that as strong as my anxiety was when it was telling me to do the old behavior, it was wrong. It was very real, but it was not true. It was not guiding me in the right direction.

And that new thought I noticed? I learned that thought prompts me to do that old behavior. And you know what? In this situation, that thought—that assumption—was incorrect.”

Why Is This a Big Deal?

Knowledge of Behavior gives me a new rule to follow. And as long as (a) I am presented by a very similar situation, (b) I am not more triggered this time, and (c) I remember my new rule, I’ve got a shot at doing it differently.

Knowledge of behavior gives me another set of rules to put on top of the rules. An app to work around a flaw in the underlying code. But it isn’t a fix. I understand how I tick, but I can’t change the tick into a tock.

Self-Knowledge—over time—changes the underlying code itself. Rules become simpler, not more complex. Behavior changes not because of running the new rule on top of my other rules, but because I perceive myself, others, and life, differently. I am literally assembling reality in a new, more nuanced, more complete, less distorted way.

Harvard professors Bob Kegan and Lisa Lahey call this “increasing mental complexity.” Read chapter 2 of their book, An Everyone Culture. They are experts in adult development, and therefore personal development. I literally consider that chapter a must-read, and alone worth the price of the book.

Self-knowledge is the process of ironing out the bugs and distortions embedded in my IOS, out of sight, out of my typical consciousness. As the bugs and distortions inherent within my IOS are ironed out through practice, through leaving my comfort zone, through reflection and contemplation on what happened and what is giving rise to all this… my actions, my behaviors, simply change. And sustainably.

My behaviors belie my self-knowledge. Want to change behaviors? Change the system. But butt in chair and hands on keyboard and light up that screen… and code.

It’s not fast. It’s not fancy. It’s messy. It’s scary. But it is exhilarating (at times). And it works. And I have to do it myself, but it is damn hard to do it alone. And that’s why I have my peer development group, my cohort, meeting twice a month for two hours in this thing we call an SW. But, as I’ve already said, SW’s go sideways. It isn’t a matter of “if”. It’s more a matter of “when”.

Tell-Tale Signs of a Peer Development Group Going Sideways

I’ve already given you one marker—boredom. Show me a peer development group that has gone flat, and I’ll show you a peer development group where radical candor has collapsed and people are no longer challenging one another to leave their comfort zones and enter the unknown, the discomfort zone, the learning zone. They are checking the boxes of the process, dutifully filling our their practice tracking form, are drunk on their new elixir of their newfound self-awareness, and the pursuit of self-knowledge is lost.

I’ll give you one more marker.

All you need to do is watch the questions the listeners ask of the presenter. We are all wired to be problem-solvers. But an SW–the way we do them at least–is not a problem-solving meeting. It is a problem-finding meeting.

So, when a peer development group falls asleep at the SW wheel, they are asking lots of questions about the situation. They want to understand the situation better. They are also wondering about the behavior–the old and the new. So they are asking questions like, “Did you think of doing this or that?” In other words, did you think of doing a different behavior?

Situation.

Behavior.

Off to the races the cohort’s problem-solving minds go! Oh, so exciting. Let’s help our friend here fix this situation. Oh boy! Oh boy!

The group in all their problem-solving zeal has totally lost the plot and the purpose.

The purpose is to help the person gain self-knowledge. Self-knowledge means probing around their IOS. It is about asking questions regarding how much anxiety they experienced, what label they’d put to it to describe it, what was the anxiety telling them to do, what thoughts did they notice that have been there all along and yet they never noticed, what assumptions and beliefs have been justifying the behavior, etc. Our job is to get them to think about their thinking.

This is can be messy and uncomfortable. So no wonder we stay with…

Situation.

Behavior.

It is surprising how little we need to understand about the situation when we aren’t trying to solve the situation/problem. We are trying to support the person in finding the problem… in their IOS. So we need to drop the inquiry down a level. Therefore, that is where the questions and comments should be focused. Here is what I might be thinking, as I’m listening to the presenter and wondering how I might apply radical candor in supporting them…

- Am I clear on what self-knowledge they gained, if any?

- Are they clear?

- Did they actually run a test, or are they backing into one so they can “check the box”?

- I wonder how much anxiety they felt, how far outside their comfort zone were they?

- What was the fear, I wonder? Are they clear on that, or is there perhaps something more or different?

- What are the thoughts a person would have that would give rise to that old behavior? Do the thoughts they are reflecting on make sense, based on this?

- What questions do I need to ask to get clear on this?

- What thoughts or feelings about all this are coming up for me, that I could share with them that might be helpful?

- Am I personally triggered by what they are sharing? How is that affecting what I am seeing

- How uncomfortable is this making me? How does this apply to me?

- Is my own discomfort and the potential of making them uncomfortable holding me back from radical candor?

These types of questions are simply a handful of examples of what makes for a powerful peer development group. And far, far from boring.

IOS. Not the Situation. Not Behavior. The latter two are secondary and can be useful. But don’t stop there.

When the primary focus is not IOS, the peer development group is drifting. It is as common as the sun rising in the morning, and it is something a peer development group must continually attend to.

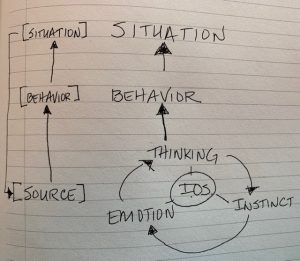

The attached photo is from a page of my notebook this week, sketched during an SW this week. Had you been there, you would have seen me holding this diagram up in front of my webcam, teaching the above. Encouraging people to drop their focus and their questions down past “situation,” down past “behavior” even… into that messy, uncomfortable yet liberating realm of “source”–our IOS. Our thinking, instincts, emotions, and the interrelated interplay amongst them… and the distortions and flaws therein.

The attached photo is from a page of my notebook this week, sketched during an SW this week. Had you been there, you would have seen me holding this diagram up in front of my webcam, teaching the above. Encouraging people to drop their focus and their questions down past “situation,” down past “behavior” even… into that messy, uncomfortable yet liberating realm of “source”–our IOS. Our thinking, instincts, emotions, and the interrelated interplay amongst them… and the distortions and flaws therein.

And more from more than one person I heard the same refrain.

“Why didn’t you tell me or us this before?”

And my answer?

“Because I didn’t yet fully understand this.”

Now, I am sharing this with you. And I hope it serves you well.

Looking Back

If you enjoyed this post, look back to this one, Seven Questions: Personal Development Made Practical. In the post you read just now, I’ve given you potential solutions and understanding into what you can do to bridge the insight you gained (or will gain) from those seven questions into action. And I’ve also given a much deeper glimpse into why your answers to questions 2, 3, 4, and 5 MATTER so much in your ability to accomplish the most important thing you want to accomplish this year.

Looking Forward

The most important things I hope you take from this post are:

- That self-knowledge is power, and not the same as self-awareness.

- That self-knowledge is a stoic endeavor, requiring us to continually leave our comfort zone.

- That self-knowledge means provoking our IOS so we can come to know it.

- That self-knowledge naturally and sustainably changes behavior over time.

- That receiving the support of others is essential, that you need a peer development group even if that is only one or two other people.

- That radical candor is the engine of a great peer development group, and must continually be attended to because it is both hard to summon and hard to sustain.

Lot’s more coming. I hope you choose to hang for a while.

Know someone who might benefit from this? If so, I’d appreciate if you’d pass this along. The more people this post benefits, the better. 🙂

Be well, and have a great week.