Acknowledging the emotions of others builds psychological safety and opens a gap for magic to happen. I want you to find out for yourself. I want you to try it. I want you to know for yourself. And in this article, I will try to inspire you to give it a go and give you a basic approach that you can make your own.

What I’m about to tell you is based on a true story. This happened just yesterday…

Anna was visibly upset at the news: she’d just found out that four of her peers were leaving her personal development cohort. (Anna isn’t her real name, of course.) This was a big deal for her because Anna is slow to trust. And she’d learned to be very vulnerable with this group, and she was really starting to move from strength to strength in her personal development work.

And now this.

Something she’d benefited so much from and had come to value so much was being taken away…

Picture yourself in this group. Anna is not only slow to trust, but she’s also intense. And exceptionally bright. A warrior, in my opinion. And now distressed. Mix those four things together, and put yourself there in her presence, in a group dynamic.

What would you do, sitting there in that group?

Most people in this situation will do one of two things.

1. Shrink away and withdraw. Leave it to others to deal with, pretend like it is not happening, let it pass. Shift nervously. Check the smartphone. Something. Anything. Just not this.

2. Connect and comfort. Reframe. Encourage. Look on the bright side. “It will be okay.” “You shouldn’t feel that way…” Let me get you out of this as quick as I can.

Both things happened. Two-thirds went silent. One-third swung into let’s-make-you-feel-better mode. But no one was attending to the this part of the situation. There was denial of this. There was let’s get through this. But there was no exploration of this and therefore no real support of and for Anna.

Anna acquiesced to the comfort, and we moved on. However, Anna was still clearly distressed. She needed a stitch and we’d given her a band-aid. And this is the way it often goes down, isn’t it, in so many groups?

This is social conditioning: to dismiss emotions and the person having them. And so on we went with the agenda. We moved on — to all intents and purposes — without Anna.

Except. Except in this group, the agenda is personal development.

So I said, “Can we go back to Anna?”

Backdrop

This is the time of year where we move people amongst cohorts whilst adding new cohorts. At this company, we are moving 19 people and we are bringing in 48 new people. This change process isn’t always easy. And it certainly wasn’t easy on Anna.

One regret I have is that we’ve not trained the good folks in these cohorts how to cultivate psychological safety. We throw them into the deep end of the pool, and then use situations like this to model what we should have taught up front. It’s not the best way, and I will be writing a course on precisely this. But there is currently no course, no prior training, and right here is Anna. I say this because it isn’t that the cohort is failing, but that we’ve failed to train the cohort.

Until now.

Back to Anna

We turned our attention back to Anna, and I said,

“Anna, it would be natural to feel a sense of loss, of grief. Say more about what you are feeling, tell us what is distressing about it.”

Anna went on to describe what it had meant to her to come to trust these people who would listen to her without judgment. That — out in the corporate world — she felt she had to feel invincible, invulnerable. Here, in her trusted cohort, it wasn’t like that. She was learning to soften. In the softening, she was finding true strength. And she felt like she was losing all this support with the new changes.

Anna was talking her way to clarity: She was starting to feel and acknowledge her own feelings. To find them. To make meaning of them. To not push them away.

Then something that belies her prior work in personal development then happened. I could see this warrior shift. She summoned something I’m not sure even she knew or knows what is.

If you’d been there, really watching, you could see her start to search inside herself. Her eyes fell downward, and it was as if she was searching for a missing piece. Yet she was fully engaged. Also, the group was starting to get the hang of this, and they engaged. Not in what they said, but in the tangible shift of now actively pulling for her to find that missing piece.

She found it.

Emotions Contain Information

One of the concepts Sara teaches in her How to Work with Emotions course is “emotions contain information.” It is such an important concept, and so few of us know that. And fewer still know how to do it in the moment that matters.

To pull information out of emotions, we must turn into the emotions. That’s what Anna was doing, and she was doing it instinctively. In the moment. I was somewhere between awestruck and dumbstruck. And she looked up and said,

“I don’t know why you don’t move the two of us with experience into the other cohort and move all the new people into this cohort.” She paused, and considered, and then said, “This would make this easier for me. The experienced people will understand me better, faster. They will have some appreciation for my struggle. I can trust more there.”

My response was simple and straightforward,

“We had not thought about doing that. It simply didn’t occur to us. And we can run that idea up the flag pole.”

Things shifted. The group was now all in and activated. When we turn in to emotions and start using them, the air can start to bristle with opportunity. It’s nascent, alive space. It is uncertain and unknown and therefore an adventure. It can call people. Other options emerged, and an even better solution emerged as everyone came online and actively participated.

Afterward, we did “run it up the flag pole”. Those we ran it past really liked not just accommodating where Anna was at in her journey — which was at a pivotal point — but that the solution also worked better for everyone.

The two cohorts involved with this change actually ended up stronger as a result.

It was a better answer. And — following the typical rules of social conditioning that avoid turning into emotion — it would have been missed.

But equally important: not addressing the emotion would have diminished trust and dismissed Anna. It would have collapsed an opportunity for Anna to “search inside herself” and to develop that capacity further. Anna would have been left feeling misunderstood, perhaps shamed, and certainly not cared for.

Circling Back with Anna

The next morning, I let Anna know everyone liked her proposed solution. Here was her response…

I can’t thank you enough for helping me explore the thoughts behind my feeling disappointed and confused. Oftentimes emotion comes from thoughts that aren’t fully developed, but [rather from] instinct (amygdala)! I so much appreciate you helping me get to a better conclusion and recommendation, and then taking that [up the ladder] for their thoughts…”

I share this with you so you can appreciate what you have the potential to do for people when you acknowledge their emotions. I hope this inspires you to give it a go because it helps a fellow human being who is suffering. And, it may help them a lot more than your very best consolations.

What Makes for a Top Flight Team

Google spent a lot of time and money studying the difference between their top-flight teams and their teams on the bottom end of effectiveness. The initiative was called Project Aristotle and Charles Duhigg talks about it in his book, Smarter, Faster, Better in Chapter 2, Teams, which focuses on psychological safety in teamwork and group cooperation. (I’d recommend that book for that chapter alone.)

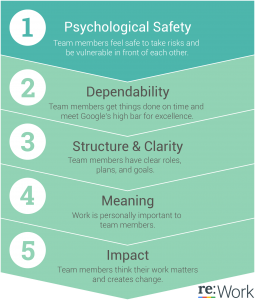

Google found that one key driver of team performance is psychological safety. It was one of the five most important differentiators between highly effective groups and ineffective groups. They placed it in the #1 position in the diagram of their findings (over to the left).

Google found that one key driver of team performance is psychological safety. It was one of the five most important differentiators between highly effective groups and ineffective groups. They placed it in the #1 position in the diagram of their findings (over to the left).

Acknowledging one another’s emotions was one practice they noted in teams that had a high degree of psychological safety. It is one of the simplest things in the world to do. But it isn’t common. And it is not necessarily easy — because when you acknowledge emotions you are stepping into the unknown. And there are parts of each of us that get scared to death with that wild, crazy-arsed notion. The unknown? Phooey to that!

It’s Not Just About Teams

The notion of psychological safety isn’t limited to teams. It is just as relevant in our personal relationships. However, there is a much deeper concept that can be worked with. Sara, a psychologist who is an expert in Attachment Theory, has taught me a little about a very big concept called “secure base”. Sounds like a good thing to have, and it is.

We can become a “secure base” for ourselves, and we can be a “secure base” for others. This isn’t just about business. This is about healthy interpersonal relationships wherever they are. This is about healing, integration, cooperation, unconditional love, compassion, common humanity, the capacity to serve, and other incredible things.

Thus, one small but mighty thing you can do to make this world a better place is to start acknowledging the emotions of others. When you do, you give them a sense of a secure base they can draw on as they weather their internal storm so they can stay with those emotions, search within them, and pull the information out. That’s what we were doing with Anna, and that can happen anywhere.

What Makes It Hard

1. What makes acknowledging the emotions of others hard is that it brings us up against our own emotions. We can’t be with the emotions of another and not be with our own emotions. And let’s face it, we’d rather check Facebook or even the weather than face our own emotions, right?

2. What makes this hard is we are afraid we will make the other person feel worse or actually cause harm. We fear they will suffer even more than if we acknowledge the emotion and shine the light on it.

3. What makes this hard is that the whole endeavor of working emotions is entirely unpredictable and potentially messy. Emotions aren’t linear, aren’t logical, and when they start moving there is just no telling where they will go, how intense they will be, and how long we will be with them.

4. What makes this hard is attending to emotions throws us off our intended “agenda”. Let’s just say in the typical meeting agenda in organizational life, emotions don’t fit well because the agenda is packed full and assumes the human being operates like a machine. And then we wonder why most meetings are entirely boring, ineffective, go nowhere, and seem to be a huge waste of time.

So, yes, attending to emotions can powerfully throw us off our written agenda… depending on what our agenda is. We may need to reframe our notion of “agenda”. Apparently, they have in those high performing teams at Google. Acknowledging one another’s emotions is part of their bigger agenda. And it makes sense because you can march right through the written agenda, checking off all the boxes, and then no one does a damn thing that was agreed to. Because their emotions were never included, and therefore they were not included.

Like it or not, human beings are emotional beings. So we might as well get really good at working with emotions.

5. The bottom line? What makes this hard is that it scares us. We are afraid of what we might uncork, we are afraid of whether we have the skills to deal with it, we are afraid of what the ask might be, we are afraid we will be the ones expected to have the answers, and on and on. To do this isn’t just making the other person vulnerable. We ourselves are being vulnerable. That is what scares us. And that is also what connects us.

The first step is to step over the fear and embrace the vulnerability of it. How might I en-courage you to step over that fear? What might help is for me to share a very basic approach that you can review and make your own. But this is an article, not a course. So don’t think of what follows as an end-all-be-all. This is just you and me talking, and I’m sharing what comes top-of-mind that might help you summon your courage, and step over that very natural fear.

Here goes.

A Very Basic Approach

You don’t need training, really. Just a willingness to learn and a willingness to pay the price of some discomfort in order to give and receive the many benefits of doing so. It really is more of an intention than anything, a willingness to attend to another human being and their needs.

You get good at this by doing it, often somewhat poorly at first. Someone once asked Sara how you get good at working with the emotions of other people. Her reply? “That’s easy. Get it wrong 100 times.” We want a shortcut, a book, an app, a hack. There isn’t any. As Yoda says to Luke, “Do or do not. There is no try.”

That said, these basic steps and concepts might serve to get you started. Trust yourself to fill in the gaps and improvise along the way.

1. See. Observe emotion in others. For some of us, this is easy. For others, it is difficult. For a lot of us, it is somewhere in between.

2. Observe. Notice your reactions to seeing and feeling the emotions. What are your tendencies? Do you withdraw, recoil, disengage, shut-down? Or is your impulse to rush in and “fix it” and “comfort”? Observe your impulses, your physical sensations, your thoughts, and your own emotions. This step alone is worth spending some time doing — over and over again — before you move on to the actual acknowledging of the other. The step before that is to acknowledge yourself.

Notice any justifications you are using to not acknowledge their emotion. Such as, “Asking them about their emotions will make them feel worse.” Ask yourself, “Do I know this to be true, or is this something I’m telling myself to justify avoiding this?” Likewise, if your tendency is to go into fix-it or and comfort-them mode, notice what you tell yourself to justify doing so. And ask, “Is it true? Is this always the most helpful thing to do?”

I am intentionally belaboring this one point of observing how seeing and experiencing the emotions of others affects you physically, mentally, and emotionally. I am belaboring it because you’ve got to put your own oxygen mask on first before helping the people around you. You don’t want to rush this, yet you don’t want to get stuck here at 2.

If you rush this part, your ability to attune to the other, your ability to attune to your own higher self (which always knows what to do), and your sense of timing will all be compromised. Having these capacities online is a big help as you move to 3, below. But don’t get stuck here at 2.

3. Decide. Decide whether to acknowledge the other person’s emotion. Do you want to follow your very normal desire to avoid this, to avoid the possibility of making them feel worse, etc…. or do you want to lean in? Or, if your tendency is to “fix-it” or “comfort”, would you be willing to acknowledge and explore instead, knowing that this is going to extend the window of discomfort while your tendency is to close it ASAP.

Initially, it is not as important what you choose to do but that you have started making active choices. This, alone, is a lot of progress.

If you decide not to bring it up or do it differently, acknowledge that you are making progress. You are making progress because you are (a) seeing, (b) observing, and (c) deciding. That is quite a step forward from unconsciously recoiling or reflexively “fixing”. Keep noticing the way you feel and the thoughts you have after making the choice not to acknowledge the emotion. And have self-compassion for yourself as you acknowledge those. Almost inevitably at some point you will lean in.

If you decide to lean in…

4. Acknowledge. Acknowledge what you see or sense, or that you see or sense emotion.

“Otis, you seem to be feeling ______. I wonder what’s going on for you?”

Or

“You seem to be experiencing some emotion, what’s happening?”

Or

“Before we move on to the next thing… Otis, something seems to be coming up for you. Is this the case? Are you feeling we are missing something?”

Whatever feels natural to you and appropriate to the moment. Keep it short.

5. Improvise. Since you don’t know exactly what’s going to happen, all I can tell you is at this point you will need to improvise. You will need to roll with whatever comes up. Trust that you can. And trust that the only way to get really good at it is to do it when you are not that confident that you can do it well at all. If you are like most people, you vastly underestimate your capacity to roll with it. To improvise.

While I cannot tell you where it will go, I can give you the typical scenarios:

1. You misread the situation, and they say nothing is going on and you feel or look stupid.

2. You read the situation right, and they say nothing is going on and you feel or look stupid. And now confused.

3. They break down, and you have a right royal mess on your hands.

4. They get angry at you for embarrassing them or calling them out, and you have a right royal mess on your hands.

5. Or, like Anna, they lean in. They take the leap. They step through the door you opened for them.

By the way, 1—4 are common fears, but not common experiences. Not so long as you exercise good judgment about when to do this and when not to. Start small when you are beginning. Work outward from there.

Five is much more common. When you do this for someone, you are giving them air. And my experience is, if your motive is pure and your heart is open towards the person, it goes at least “good” if not “well”.

What if 1—4 come to pass? I often use humor. “Well, that didn’t go so well. I’m sorry. Shall we move on?” Often there are some chuckles or laughter. But, again, 1—4 are very rare in my experience. They happen 100x more in our minds than in reality.

Here’s what is typically more important at this point…

6. Self-Regulate. As the other person is talking, keenly notice any tendency you have to prematurely want to make it better for them or to end this as quickly as possible. If you move to “fix it” or “comfort them” or if you try to end the discomfort too soon, you may very well — with the best of intentions — collapse the learning + healing + discovery + growth for them. So…

Don’t “collapse the tension” too soon. Resist making them feel better or offering help until their cup is empty (or until they are clearly suffering too much). Some suffering can be healing for them, and there is some suffering involved in them searching around in their feelings.

Honestly, your rush to make them feel better is often a rush to make you feel better. Watch for this. You may be confusing your suffering with theirs, and maybe adding yours and theirs together such that the sum feels overwhelming to you. Not them.

7. Check-In. How do you know their cup is empty? You ask.

“Is there anything more?” And you keep asking that until you and they know the well is empty or the time is nigh. And you stop.

8. Help. Ask whether they want help. “Is there anything I can do (or we can do) to help?” Then be quiet. Let them tell you before you offer anything to them.

The more that comes out of them, and the less that comes out of you, the better. This way, they are in control. You are respecting their feelings, their wishes, and their timing.

9. Reflect. Reflect on how it went, and what you learned. Your reflection may be yourself alone. Or it may be with the other person or group right then and there. Or the reflection may come later. Just don’t skip this step, at least with yourself. It primes you for the next time, and positions you to keep getting better and better at it.

What If This Goes Pear-Shaped?

It probably won’t. But, I do know how the ego works. It is fear-based, and security oriented.

I find it helpful to tell my ego we have an escape plan. “We can abort,” I tell my ego. “I’ve got your back.” And it seems to settle down a bit and the fear of leaning in becomes a little more tolerable.

How? How do you abort?

You can stop it with one, heartfelt expression.

“This doesn’t seem to be going too well. I’m feeling we should end this. How about you?”

If they choose to abort, you might say something like, “Thank you for trying. I’m new to this. And I’m sorry it didn’t go so well.”

And maybe, “I won’t try that again unless we talk about it in the future and both think it is a good idea. Again, my apologies.”

I’m not giving you an abort strategy because you will need it. I’m giving it to you so your scared self will have a binkie to hold on to whilst that big, brave, kind, caring, insightful, and compassionate part of yourself tries to be of service to another human being who is struggling.

Over to You

Stephen Porges, known for the development of the Polyvagal Theory, is noted to have said something like…

If you want to change the world, start by making it feel safe.”

Want to make the world a safer (and better and more connected) place for others?

Acknowledge the emotions of other people.

Want to learn to acknowledge the emotions of others?

Start.

Set the intention to get good at this.

Notice an opportunity that seems do-able.

Leap.

And give it your all.

Your all will be good enough. Work from there.

It is no more complicated than that.

Try it. And I’d love to hear how it goes.

You and I can change the world.

We start here.